Google has enjoyed something of a love affair with Bletchley Park in recent times,

Now known as the historic site of secret British codebreaking activities during WWII and the birthplace of modern computing, the secret work achieved at Bletchley Park is believed to have shortened the war by two years.

Perhaps the most famous story to later emerge was the breaking of the code of the German Enigma machine, but Google are keen to remind us all of the debt we all owe to this Buckinghamshire backwater.

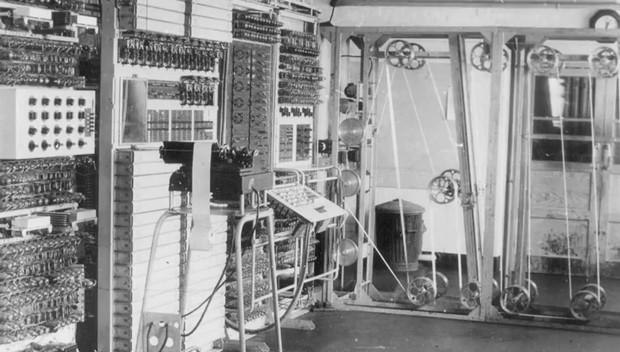

Codebreaking machines like Tommy Flowers’ Colossus and Alan Turing’s Bombe proved to be forerunners of modern computers, and Google seems keen to celebrate that heritage.

Last year, Google backed an appeal to restore the derelict Block C at Bletchley Park and also provided cash to buy key papers by Turin.

Google feel that the company owes its existence to Turin’s work, as Peter Barron, head of external relations for Google in Europe, the Middle East and Africa told the BBC: “I don’t think it is an exaggeration to say that without Alan Turing, Google in the form we know it would not exist”

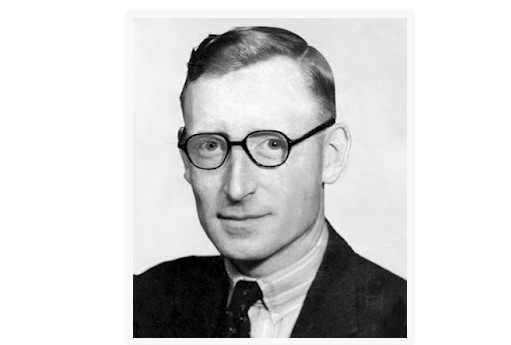

In last night’s blog post, Google decided to pay tribute to Tommy Flowers, who created the Colossus, the world’s first programmable, electronic computer.

The computer proved to be a vital asset during WW2, as Google observe:

When Flowers proposed the idea for Colossus in February 1943, Bletchley Park management feared that, with around 1,600 thermionic valves, it would be unreliable. Drawing on his pre-war research, Flowers was eventually able to persuade them otherwise, with proof that valves were reliable provided the machine they were used in was never turned off.

Despite this, however, Bletchley Park’s experts were still skeptical that a new machine could be ready quickly enough and declined to pursue it further.

Fortunately Flowers was undeterred, and convinced the U.K.’s Post Office research centre at Dollis Hill in London to approve the project instead. Working around the clock, and partially funding it out of his own pocket, Flowers and his team completed a prototype Colossus in just 10 months.

The first Colossus came into operation at Bletchley Park in January 1944. It exceeded all expectations and was able to derive many of the Lorenz settings for each message within a few hours, compared to weeks previously.

This was followed in June 1944 by a 2,400-valve Mark 2 version which was even more powerful, and which provided vital information to aid the D-Day landings. By the end of the war there were 10 Colossus computers at Bletchley Park working 24/7.

Sadly, Flowers never gained the recognition he deserved after the war because all mention of Colossus was forbidden by the Official Secrets Act.

Eight of the machines were also dismantled, with the remaining two being shipped off to do secret intelligence work in London up until 1960.

It was only in the 1970s that the story could be told, and it’s something that Google rightfully feel should be celebrated with their own short film about Flowers and the Colossus computer.

It’s a fascinating document and a salutary reminder how grateful we should be for the wartime work done at Bletchley Park.

Update: Here’s some archive footage of Tommy Flowers talking about his work:

Here’s two videos about the rebuilding of Colossus:

Mike,

I’ve been studying this for years, and been 3x to Bletchley (from NYC). The work done there (de-cryption, computing, mis-information, strategic) was simply astounding, and the wider world is just now beginning to appreciate the significance of it.

Thanks,

Eric